In the following article our historian, Wendy E. Harris, has sketched the history of the Shawangunk region going back hundreds of years. Many of our historical resources are shown in photos that accompany the text.

We are fortunate to have much to photograph. Many of the early Dutch-style stone houses built here in the colonial era survive throughout the region. In fact, of the 56 sites in our region listed on the National Register of Historic Places, 13 were built in the early 1700’s or before.

Many listings are farmsteads, such as the Van Wagenen stone house (1751) and farm complex in the Rondout Valley, and the Johannes Decker stone house (1726) and farmstead in the Wallkill Valley.

Much of our history involves the industries that flourished here for many years. The National Register includes sites with artifacts and remains of the D&H Canal at High Falls and Ellenville, the cement industry at the Snyder Estate Natural Cement Historic District and the Binnewater Historic District in Rosendale, the O&W Railroad in Wawarsing, and the Tuthilltown Gristmill in Gardiner.

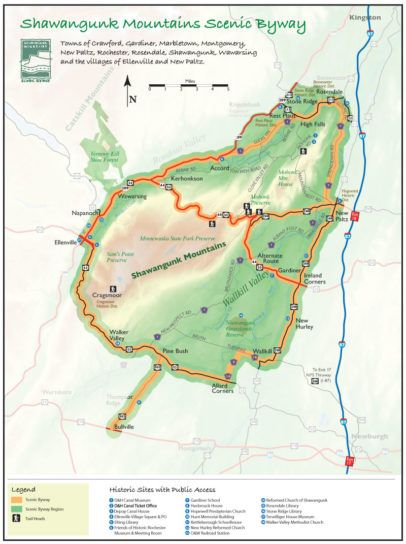

In addition to these historic resources of national significance, we have many listed on the state and county registers. Further detail and discussion of historic resources are included in the The Shawangunk Mountains Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan.

The Shawangunk Region: A History

by Wendy E. Harris

The history of the Shawangunk Mountains Region goes back to about 11,500 years ago, when the last glaciers were receding from the landscape and the Native Americans who lived here traveled back and forth over the ridge between the two rivers that give the Wallkill and Rondout valleys their names.

For thousands of years, Native American settlement was shaped by waterways which served as travel and trade routes, fishing areas, pathways for following game and sites for cultivation. Our rivers were said to be “lined with corn-planting grounds”.

Evidence also indicates that the ridge itself was an especially attractive area for the region’s original inhabitants, perhaps for hunting and gathering various foodstuffs such as berries, nuts and medicinal plants.

The ridge must have been an important landmark in a world of footpaths and rivers, visible from the Hudson River as well as from the mountains lying to the northwest. Native American travelers followed a number of trails over the ridge. One such footpath, the “Old Wawarsing Trail,” connected Native American settlements on either side of the mountain and crossed the steep eastward facing escarpment at a break near Indian Cave, passed close by Lake Awosting, and finally reached the Rondout floodplain just outside of the hamlet of Wawarsing. The alignments of other trails became the basis for many modern roadways including Route 209, Route 52, and Routes 44/55.

The first Europeans arrived in Kingston in the early 1650’s. Although we are now accustomed to defining the region’s early settlers as “Dutch,” only a portion actually came from the Netherlands. The settlers, in fact, encompassed a heterogeneous mixture of French, Walloon, German, Flemish, Scandinavian, and English heritage. During these first years, the settlers and their Native American (Esopus) neighbors attempted a peaceful co-existence. These efforts, however, were almost immediately doomed by conflicting concepts of land ownership.

Tensions culminated in the First and Second Esopus Wars, spanning the years 1659 to 1664. During the wars, the settlers pursued the Esopus down the Wallkill and the Rondout rivers.

It was during these expeditionary journeys that the settlers may have first fully grasped the region’s enormous agricultural potential.

English forces conquered New Netherland in 1663 and in 1668 English soldiers at Kingston were awarded portions of land within present day Marbletown.

Other settlements soon followed. In 1677, portions of the towns of New Paltz, Lloyd, Esopus, and Rosendale were granted to 12 French Huguenots who moved from Hurley to New Paltz and began building homes in 1678. Settlers are believed to have been in the Town of Shawangunk as early as the 1680’s and by 1700 settlers were living in Wawarsing.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the farms and villages had completely transformed the lands of the Esopus. Dutch architecture, religion and language were pervasive throughout the region well into the middle third of the 18th century. Even New Paltz’s French Huguenots came to speak Dutch before switching over to English at the end of the century.

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Dutch and French Huguenots are the homes they built of native limestone. Many of these structures can be found today along the region’s roadways, on remote farmsteads, or clustered together in the older villages.

Although early settlers were involved in the lucrative fur trade, it was apparent from the very beginning that the region’s “real riches” lay in the lowlands adjoining the Wallkill River and Rondout Creek. As early as 1683, wheat and other produce were grown for market, including trade with both New York and the West Indies. The fields to the north of New Paltz, especially in an area called “Bontecoe,” became famous for wheat production.

The milling of grain was a vital economic function. Thus, the presence of waterways that could furnish hydropower influenced the location of Euro-American settlements in the region. The unbroken forests and barrens of the Shawangunks fed numerous streams that flowed down the ridge’s slopes, joining the Rondout, the Wallkill and the Shawangunk Kill. In what is now the Town of Gardiner, the earliest recorded settlement was at Tuthilltown where a mill was built upon the Shawangunk Kill in 1745. Settlement in the Town of Crawford began in the mid-18th century, clustered around a series of mills on the Dwaars Kill and Shawangunk Kill. In the town of Shawangunk, hydropower also played a major role in the settlement of Brunswyck, Dwaarskill and Wallkill.

On the western side of the ridge, in the Town of Rochester, a cluster of mills developed on the Stony Kill and Peters Kill, tributaries of the Rondout that drained the Shawangunks’ western slope. The first gristmill in the Town of Wawarsing dates to 1702. It was constructed on the Vernooy Kill.

Many of the region’s early “service industries” —such as taverns, inns, blacksmiths, brewers—grew up along the early road system, especially at crossroads and fording places. Like mills, these facilities attracted small communities, often accompanied by a Dutch Reformed Church.

In the narrow Rondout Valley, settlement was focused upon a single roadway, the Old Mine Road (corresponding to present day Route 209). Like most roads of the time, the Old Mine Road followed an ancient Native American trail. By the 1730’s, farmers as far away as Pennsylvania and western New Jersey followed the Old Mine Road to the Hudson River at Kingston, where they loaded their produce on New York City-bound sloops.

In the Wallkill Valley, several early roadways were oriented east/west to take advantage of Hudson River landings. The Bruyn Turnpike is said to date to the 1690’s. The principal north/south route, opened in 1735, was the Old Kings Road—running through Kingston, New Paltz, and “the Shawangunk Precinct” before finally reaching Goshen in Orange County (portions corresponding to present day County Route 7). Because the King’s Road followed the west bank of the Wallkill River, New Paltz residents could connect with it only by crossing the Wallkill by scow. Another road was built on the east bank of the Wallkill River leading south by 1790 (corresponding to Plains Road and Route 208).

As the two valleys became more populated and good farmland scarce, a small number of families were drawn to the few locations on the Shawangunk Ridge where the soils could support agriculture. By the end of the 18th century, there were three communities on the ridge: Trapps Hamlet, within what is now the Mohonk Preserve; and the Mance and Goldsmith Settlements, near what is now Cragsmoor. Mountain residents raised sheep and grew flax to provide wool and linen. They raised cattle to provide leather for their clothing and equipment. Hunting and trapping were pursued for both sustenance and currency.

During the Revolutionary War, there were no engagements here between the warring armies. But in the spring of 1779, Tories, Hessians and Iroguois attacked the settlement at Fantinekill, near present day Ellenville. This was followed by murders and raids in the Town of Shawangunk and on the ridge in 1780, and the destruction of Warwarsing in 1781.

General George Washington did indeed sleep here. On November 15, 1782 he stopped for the night in Stone Ridge at the Wynkoop-Lounsbery House on his way to Kingston. His troops spent the evening at the Tack Tavern. Both structures are still standing.

The event that marked the region’s entry into the industrializing world of the 19th century was the completion of the Delaware and Hudson Canal in 1828. Built to carry anthracite coal from northeastern Pennsylvania to New York City, the D&H presented what seemed to be limitless economic opportunities to many rural communities. Villages lucky enough to be located along the canal’s route thrived. Others sprang up almost overnight, owing their existences to the canal. Within the region, these self-described “canal towns” included Ellenville, Napanoch, Port Hixon, Port Ben (East Wawarsing), Middleport (Kerhonkson), Port Jackson (Accord), Alligerville, High Falls, Lawerenceville and Rosendale.

Cheap transportation via the canal opened markets for a wide range of local products and resources. From the slopes of the Shawangunks came lumber, cordwood, charcoal, shingles, hoop poles and millstones. Agricultural products included fruit, grain, and flour. New factories opened along the canal’s route. Ellenville and Napanoch were transformed into industrial centers. Their products included pottery, axes, glass, iron, leather, paper and cutlery. Support services for the canal included stores, hotels, boarding houses, taverns, and harness and blacksmith shops. A number of communities, especially Ellenville, developed boat-building facilities.

Perhaps the most significant industry associated with the canal was the manufacture of hydraulic cement, also known as Rosendale cement. Hydraulic cement was critical to the canal’s construction because it was not soluble in water. Due either to luck or the intervention of a geologist employed by the canal company, limestone beds discovered in the vicinity of High Falls and Rosendale in 1825 were found to produce a superior quality hydraulic cement. In the following decades, a cement manufacturing district developed around Rosendale and High Falls. The various communities supported by the industry tended to cluster along the canal’s route and near limestone outcroppings. The region’s cement manufacturing factories went into a decline in the 1890’s, finally eclipsed by the manufacture of the faster setting Portland cement.

Like the cement industry, the quarrying of millstones from Shawangunk conglomerate also developed as a result of the ridge’s geological properties. The quarries were located on the northwestern slope of the Shawangunk Ridge, concentrated in a strip that extended from Kerhonkson to High Falls. Approximately 350 tons of millstones were exported over the D&H from these towns each year and most of the nation’s millstones came from the region.

Owing their existence to the canal, as well as to Hudson River shipping (and later to the railroad) were a series of industries that entailed the exploitation of the region’s forests. Perhaps the most widely dispersed across the region was the tanning industry, based upon the harvesting and processing of hemlock bark. Ironically it was only the bark which was sought, not the tree. But thousands of acres of hemlocks were used for this purpose.

Tanneries also required enormous amounts of pure water to fill the countless tanning vats that were used in the process. By the 1850’s almost every creek in the Rondout Valley hosted a tannery. There were tanneries at Wawarsing, Honk Hill, Samsonville, Lackawack, Napanoch and Ellenville as well as on the Shawangunk Kill near Pine Bush, the Verkerderkill near present day Walker Valley, and the Wallkill River, opposite Springtown. Tanning continued in our region through the 1880’s.

Canal records from the mid-19th century provide a glimpse of several other commodities harvested on the ridge. Charcoal was used by blacksmiths and for the production of pig iron. Early settlers at the Trapps Hamlet engaged in its production. Shingle making was also an important local industry, as indicated by the place name “Shingle Gully,” given to a ravine located on the mountain’s western slope just above Ellenville.

Hoop pole production and sawmilling developed in the wake of the destruction brought about by the tanneries. Numerous water-powered sawmills soon appeared along the mountain streams, processing not only the discarded hemlocks but also spruce, pine, and hardwoods. An immense amount of lumber, timber, and cordwood was shipped on the canal between 1836 and 1866.

Hardwood saplings often replaced the hemlocks and this became the impetus of a local hoop manufacturing industry. Wooden hoops were fashioned from saplings and used to bind kegs, casks, and barrels. Beginning in the 1840’s and 50’s, and reaching its peak in the late 1880’s and early 90’s, the industry is said to have shipped fifty to sixty million hoops out of the region annually. At one time, the largest dealer of hoops in the country was located in Ellenville, shipping hoops all over the world. The hamlet of Kripplebush, in the Town of Marbletown, was another important center for hoop making.

Crossing the ridge remained a difficult undertaking until the middle of the 19th century. One road, built in 1825, corresponding in part to present day Mountain Rest Road, crossed the ridge linking the communities of Canaan and Butterville to Alligerville. Initial construction of the Newburgh-Ellenville Plank Road began in 1849. Running along an alignment that would later become Route 52, it passed directly through Pine Bush and was largely responsible for the initial growth of that community. The 32-mile road was built of rough hemlock planks nailed to sleepers that were laid on the ground. In 1869, maintenance of the now rotting planks stopped and the road was allowed to revert to mud and dirt.

The New Paltz-Wawarsing Turnpike was completed in 1856. It was a toll road, running from the bridge over the Wallkill at New Paltz, westwards through Trapps Hamlet, and finally terminating in Kerhonkson at the D&H Canal. During the 1850’s it was filled with farmers and drovers taking their produce and cattle to Hudson River landings. Anyone wishing a night’s lodging could stay at Ben Fowler’s hotel and tavern, located just south of Trapps Hamlet.

The era of the railroads began in the late 1800’s. The Wallkill Valley Railroad was completed as far as New Paltz by 1870. The New York and Oswego Midland Railroad (afterwards the New York, Ontario and Western Railroad or “O&W”) also reached the region at this time—one branch extending as far as Pine Bush by 1868 and another branch arriving in Ellenville in 1871. It included a tunnel drilled through the base of the Shawangunks near Wurtsboro in 1871. The advantages of railroad transport were inescapable and in 1898 the D&H Canal Company signed an agreement with the Erie Railroad to transport its entire output of coal. By 1902, the O&W had built track extending between Port Jervis on the Delaware River to Kingston on the Hudson River, thus duplicating the route of the now nearly extinct D&H Canal.

For farmers on both sides of the mountain, accessibility to railroads was a virtual guarantee that their dairy products and produce would reach the New York City market without spoiling. The fields surrounding New Paltz were filled with new orchards. Visitors reported peach, pear and cherry trees, vineyards, and acres of berries including currants, strawberries, blackberries, and raspberries. New Paltz was now “a great fruit producing town”. The village of Gardiner, a community born with the railroad, was now the preferred shipping depot for about 30 local growers.

Creameries were established adjacent to the depots at Bullville, Thompson Ridge, Pine Bush, Wallkill, Gardiner, New Paltz, and other smaller communities. Milk shipped in the afternoon in the Wallkill Valley was in New York City households by the following morning. The most famous dairying enterprise in the region was the 2000-acre home farm and condensed milk factory of the Borden Milk Company in Wallkill. (Remember “Elsie, the Borden Cow”?)

On the ridge, the gathering and distilling of wintergreen and huckleberry picking were two of the more important occupations. Wintergreen, which grows in the mountain’s many shaded and moist ravines, was used for flavoring and for medicinal purposes. Its leaves were gathered and brought to local “stills” where it was converted into oil.

By 1871 huckleberries (the word “blueberry” being reserved for cultivated varieties) became one of the Shawangunk Region’s major items of export. The “patch” extended from Lake Mohonk to Sam’s Point. An 1899 map shows at least three separate huckleberry picker camps immediately west of Lake Maratanza. Like the Native Americans before them, the huckleberry pickers manipulated the local ecology by setting fires in order to increase yields. This particular Shawangunk Ridge lifeway continued—complete with yearly fires—well into the 20th century.

The arrival of the railroads coincided with the initial appearance of resorts for summer guests in the Shawangunks. The first hotels to open here during this era—the Mohonk Mountain House in 1870, the Mountain House at Sam’s Point in 1871, Cliffhouse (1879) and Wildemere (1887) at Lake Minnewaska, and the Mt. Meenahga House on the ridge overlooking Ellenville in 1883—catered to guests who valued the Shawangunks’ scenic beauty. Although forests directly adjoining the hotels were being clear cut for tannin bark and timber, landscaping at the hotels featured meandering carriage roads and vistas opened to create breathtaking views of the valleys and the distant Hudson.

In an effort to preserve the wilderness landscape and to become self-sufficient, the Smiley family, owners of the Lake Mohonk and Lake Minnewaska resorts, embarked upon an ambitious program of land acquisition. The more than 17,000 acres they purchased over time included agricultural lands and forests, as well as remote ravines and ridge tops.

Smaller hotels and boarding houses were located in almost every village along the O&W and Wallkill Valley lines and the entire region benefited from the development of tourism. In 1901 listings for the Ellenville-Cragsmoor area alone contained approximately 40 hotels or boarding houses.

Hotels catering to Jewish families began to appear in the Rondout Valley in the first decade of the 20th century. These were owned and operated by immigrants from Eastern Europe and Russia who were drawn by the belief that farming was a viable alternative to urban sweatshops. Because much of the land that they had purchased was unproductive, the practice soon developed of taking in paying boarders during the summer months. Some of these small boarding houses eventually grew into the famous “borscht belt” hotels of the southern Catskills region, such as the Nevele and Fallsview Hotels in Ellenville. Along side them were countless small bungalow colonies. Several of the villages along the ridge’s western slope soon developed sizeable Jewish populations.

Beginning at the turn of the century, New York State began a program of road development in the region, creating a transportation infrastructure benefiting automobiles, buses and trucks. Improvements to the Ellenville-Kingston Road (today’s Route 209) were underway in 1921. In the same year, the New Paltz-Highland Road became the first concrete road in Ulster County. The Minnewaska Trail, today’s 44/55, was built over the ridge, connecting New Paltz and Kerhonkson in 1930. Much of the original road alignment and many of the Trapps Hamlet homesteads were destroyed during its construction. Route 52, the other main highway crossing the ridge, was completed in 1936, replacing what remained of the Newburgh-Ellenville Plank Road.

By the 1920’s, automobiles had become so popular that the railroads began to falter. In 1937, passenger service on the Wallkill line was discontinued. The O&W held out until 1952 before turning exclusively to freight and then ceased operations in 1957. Conrail, which then owned the Wallkill line, cut all regular service north of Walden in 1977.

The completion of the New York State Thruway initiated yet another phase in the region’s development. By 1957, the Thruway had been incorporated into the vast Interstate Highway System. With the exception of New Paltz and Kingston, it bypassed the communities that had been serviced by the Wallkill Valley Railroad and, for the first time in history, the state’s major transportation corridor had been shifted away from the Hudson River. The Thruway also put the Shawangunks within two hours driving distance of New York City.

With their proximity to the metro area, the Shawangunks provided a perfect space to pursue such activities as hiking, rock climbing and other nature-related recreational activities. By the end of the 20th century, the Shawangunks became a tourist destination as never before.

Environmental advocacy and land trust movements emerged during the 1960’s. The result was a series of preserves spanning the length of the northern Shawangunks, including the Sam’s Point Dwarf Pine Ridge Preserve, Minnewaska State Park Preserve and the Mohonk Preserve. By the close of the 20th century, 30,000 acres of the northern Shawangunks’ nearly 94,000 acres of land were held by private and public land holding institutions.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the region still retains its rural character, small-scale businesses and much of its scenic qualities. But there is cause for concern. Open land and farmland in the Wallkill and Rondout valleys are under pressure to develop. Proposals for the Shawangunk Ridge and adjacent areas may threaten the natural systems which have evolved there over the last 450 million years. How the communities around the mountains address these issues will shape the course of history for the years to come.